Descending the Grand Canyon in a Wheelchair

The old adage, “Necessity is the mother of invention,” rings loud and true for Geoff Babb and his team at AdvenChair. In 2005 Babb was a Bureau of Land Management Fire Ecologist and an active outdoorsman, until a near-fatal brain stem stroke changed his access to the great outdoors.

The stroke left Babb in a wheelchair and with only limited use of one hand. Mountain trails and ski slopes are generally not wheelchair accessible. In fact, he quickly realized that his access to the outdoors was limited less by his body and more by his rigid wheelchair.

“I had this need to be back out on the trail after my stroke, and I knew it was going to have to be something different,” Babb explains. He began to explore the world of off-road wheelchair1, but he quickly found that the equipment required a person to have arm strength. With limited use in only one hand, none of the off-road wheelchairs on the market would cut it.

“I just started experimenting with a friend of mine, Dale Neubauer, who is a helicopter mechanic. He helped me create some parts for my existing chair to go off-road, and I started to realize what was possible. After that, it just evolved… one thing led to another,” Babb says.

Building a Wheelchair from Scratch

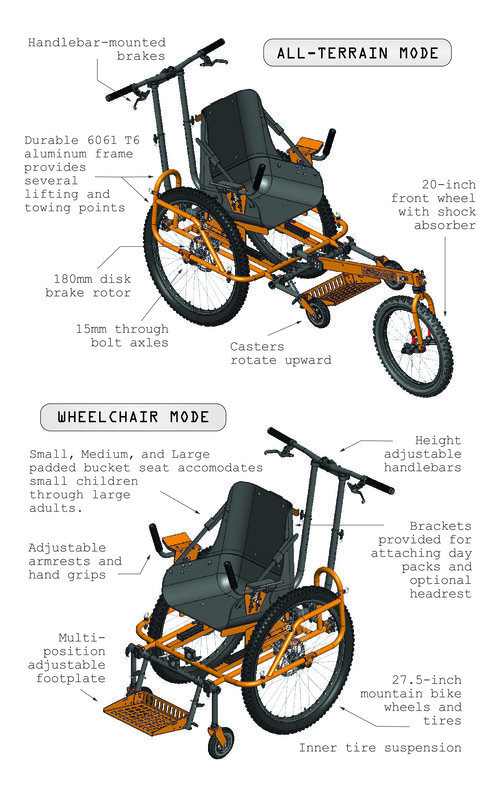

CAD drawing of the AdvenChair, all-terrain wheelchair

Babb’s first iteration of the AdvenChair was a modified version of a wheelchair. Adding beefier tires, a detachable front wheel, handbrakes on the handlebar and a harness made it so he could truly take to the trail with the help of a team to propel the chair.

In fact, they decided to take on the Grand Canyon. According to the AdvenChair team, “After bumping and grinding over countless water barriers on the Bright Angel Trail, the chair succumbed to a broken axle less than two miles down.”

The team managed to get Babb back to the rim, but it was apparent that a modified wheelchair just wasn’t going to be enough. “That failure led us to look at doing a chair that was going to meet our needs. If we hadn’t broken down, we might still be on the track of modifying an existing wheelchair, rather than creating something from scratch. That’s when Jack Arnold came into the picture,” Babb says.

With a background that started as a machinist and progressed to manufacturing engineering and eventually product development engineering, Arnold jumped on the opportunity to put his skills to good use.

“We were looking to design an off-road wheelchair from scratch, based on using mountain bike parts instead of wheelchair parts,” Arnold explains. “Wheelchair parts are generally more expensive because of the medical tag that goes with them, and they aren’t necessarily very robust. Mountain bike parts, on the other hand, are very robust and readily available. So, it was really an intriguing project.”

His work started at the heart of the whole system: the frame. Arnold found a good balance between rigidity and weight with a tubular aluminum design. It was similar to bicycle frames, so he wouldn’t have to start completely from scratch.

“I went out on GrabCAD and found a pretty good complete mountain bike assembly, available for free. I downloaded that, and used a lot of the parts from that model—the wheels, the disk brakes, the calipers, handlebars… I started borrowing parts from it, and that jump-started the design process.” [Ed. Note: model used was Freeride MTB, submitted by Joris Deschamps]

Because their design was meant for folks riding in a wheelchair, Arnold wanted to make sure the design would hold up to the stresses of both a rider and the environment.

Simulation shows maximum deflection with a 250 lb rider and a factor of three to account for dynamic loads and provide a factor of safety.

“Before I met up with the rest of the team to present my models, I wanted to do some stress testing on the frame. So, I ran some FEA simulations in SOLIDWORKS. Assuming a rider weight of 250 lbs and a factor of three to account for dynamic loads and still provide a factor of safety, I used a 750 lbs static load for the structural analysis. After a couple of tweaks, I got it to where it looked like we could make it work,” Arnold says.

With the CAD on a projector, Arnold went through the design, piece by piece, and got feedback from Babb and the rest of the team. Through several iterations, they have changed a number of things from the original GrabCAD components. For some of the off-the-shelf components, Arnold and Babb established a partnership with SRAM, a bicycle component company. “They were able to provide us with 3D CAD files of a couple of the components that we didn’t have. So, we tried to standardize our design to use SRAM components as much as possible because they’re helping us and they are very durable components,” Arnold says.

Designing for Ruggedness and Accessibility

When Arnold was building out his design in SOLIDWORKS, he took a number of factors into consideration, including a need to make the AdvenChair both rugged and light. With his background in mechanical engineering spawning from work as a machinist, Arnold knew that how the chair was made would make a difference. “I went in thinking about manufacturing,” he says. “I went in knowing what tube radius we should use, and what machining processes would be needed for the parts we were making. I kept all of our machined components simple enough for three-axis machining.”

Beyond just considering the manufacturing processes, Arnold used lots of finite element analysis (FEA) to test the design before they ever took to making physical prototypes. AdvenChair is even part of a startup program with Ansys. “With Ansys Discovery, I noticed that I was able to solve finite element analysis studies almost instantaneously while in the ‘Explore’ mode,” Arnold says.

Arnold explains that he has been a SOLIDWORKS user since 1998, so he is quite committed to the CAD program as he knows all the ins and outs by now. “Also, for producing all of the manufacturing documentation, all of the black line drawings… SOLIDWORKS works really well.” While Arnold uses the FEA in SOLIDWORKS, he is also becoming a big fan of Ansys Discovery to do more and more of his analysis work. “I used Ansys Discovery to compare the structural analysis results of the frame to the same studies I had run in SOLIDWORKS Simulation with the same exact boundary conditions… It was like having a third-party peer review of our initial stress analysis.”

He also used a more cutting-edge element of the Ansys program: generative design. To experiment, Arnold took one of the axle dropouts and ran it through the generative process. “You apply loads and constraints to the part just like any FEA, then set goals. My goal was to reduce the part weight by 40 percent. When you hit the ‘solve’ button, the program goes to work doing iterative solutions, removing material from the low stress areas on every iteration until your goals are met.”

Optimized axle geometry inspired by generative design led to a 42 percent reduction in weight of the axle bearing.

“After several iterations, you start coming up with this organic part design,” Arnold continues. “5-axis machining was not an option, not in any cost-effective way. Maybe with investment casting or molding, generative design might be worth it. But I took inspiration from the geometry that generative design created. I reworked the part geometry in SOLIDWORKS, thinning the web and adding some ribs, all while keeping the part geometry simple enough for 3-axis CNC machining. I ended up with a 42 percent reduction in weight compared to the original part’s geometry.”

Leveraging the software to go through design changes, Arnold found that things moved faster because the Ansys software didn’t require re-meshing of the entire model after geometry changes.

“While in the ‘Explore’ mode, Ansys Discovery leverages the GPUs in your graphics card which is simply brilliant! The ‘Explore’ mode is the ultimate sandbox for every design engineer. Using the ‘Design’ mode, you can quickly change your CAD geometry, then pop back into the ‘Explore’ mode and solve your analysis study without the need to mesh and re-mesh your model each time, letting you know if you are on the right path. I can solve iterations of my designs 10 times quicker in the ‘Explore’ mode than with traditional FEA process. Once I have refined my design, I pop into the ‘Finalize’ mode and use a traditional Ansys Mechanical solver to mesh and run my final study,” Arnold explains.

This process of design, test, repeat is key to how the AdvenChair is going through continuous improvement—even after their product hits the market.

A Whole New Market

According to Arnold, one of the challenges with designing an off-road wheelchair is that there are no industry standards. Combining elements from both the rugged bicycle world and the medical industry created design challenges, but also opened them up to who might use this product.

“I think the awareness of the need for this type of product has increased since we started working on AdvenChair,” explains Babb. “There are a number of older people with Parkinson’s who wanted to go back out on their favorite bike trail or go to their favorite fishing spot again.” Babb and Arnold have been looking at a number of different areas that can utilize variations of their wheelchair design, including for students to get outside with their classmates and on cruise ships to help people embark on beaches.

Babb says, “The origin of the AdvenChair is ‘adventure wheelchair.’ Originally, we envisioned something that was going to be useful in both the backcountry, as well as in town. Initially we planned for it to be lighter, but to make it useful in the backcountry it needed to be more tough than light. The next iteration will definitely be lighter but we’re also considering developing something that will be light-duty—an ‘urban version.’”

Babb and Arnold are excited about the future of AdvenChair, as they prepare for the delivery of their first production run next year. “We’re just motivated by people wanting to have experiences outdoors,” Babb says.

They plan to have more iterations before each production run, but for now they’re looking forward to learning more about how folks can use their invention.

For more on SOLIDWORKS, check out the whitepaper Simulating for Better Health.

Author note: An offroad wheelchair from Icon has been covered in EngineersRule.com here Three Wheels, 3,000 Watts and an Ingenious Designer in a Dec 29, 2017 article. The AdvenChair was meant to be more rugged and light than the motorized Icon Explore wheelchair with its stainless steel frame. The AdvenChair is modular and can be used as a regular wheelchair or put into “off-road mode” by adding the third wheel whereas the Explore has a specific use case. The heavier Icon wheelchair will be used for motorized hiking and biking, while the lighter AdvenChair is adaptable for everyday use.